Commentaar en teksten.

Inleiding

Het verhaal van de Non vind ik het mooiste verhaal uit de Canterbury Tales. Waarom? Allereerst de toon van het verhaal. In mijn vertaling lukt het mij niet om de manier waarop Chaucer dit verhaal vertelt, goed weer te geven. Chaucer weet precies de manier, waarop een Non een verhaal vertelt, in dit gedicht te treffen. Het Engels is een beetje lijzig, maar heel helder. Dit is precies zoals ik mij herinner hoe nonnen je een verhaal konden vertellen. Hoe Chaucer erin is geslaagd dit in een geschreven tekst te verwerken, is mij een raadsel. Het is ongelofelijk knap.

Het verhaal van de Non vind ik het mooiste verhaal uit de Canterbury Tales. Waarom? Allereerst de toon van het verhaal. In mijn vertaling lukt het mij niet om de manier waarop Chaucer dit verhaal vertelt, goed weer te geven. Chaucer weet precies de manier, waarop een Non een verhaal vertelt, in dit gedicht te treffen. Het Engels is een beetje lijzig, maar heel helder. Dit is precies zoals ik mij herinner hoe nonnen je een verhaal konden vertellen. Hoe Chaucer erin is geslaagd dit in een geschreven tekst te verwerken, is mij een raadsel. Het is ongelofelijk knap.

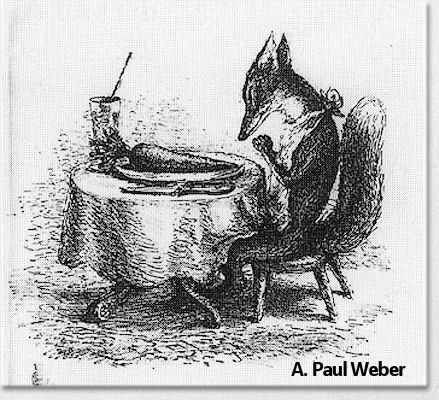

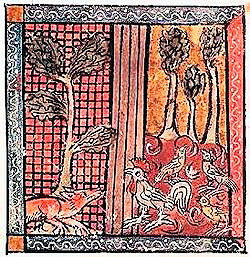

Ten tweede: het onderwerp spreekt mij erg aan en heeft mij altijd al erg aangesproken. Het verhaal van Canteclear en de Vos was alweer onderdeel van een cyclus verhalen over De Vos. Wij kennen natuurlijk onze Reintje de Vos van Willem die Madoc maakte. Maar het verhaal van Chaucer is een combinatie van het LaFontaineverhaal van de Vos die aan een Raaf de kaas weet te ontfutselen, dat veel later is geschreven, en een deel uit de Reineart de Vos van veel vroeger. Het verhaal munt uit in het gebruiken van de ambiguïteit van de tekst, waardoor het lijkt alsof beide hoofdpersonen gelijk hebben, wat op mij erg humoristisch overkomt. Hiermee heb ik in de vertaling wel een beetje gespeeld.

Reinaert de Vos is in de Middeleeuwse literatuur een figuur die vaak met de willekeur in de rechtspraak is geassocieerd. De willekeur heeft te maken met het wél verliezen van zijn haren (mantel), maar niet zijn streken. Een en ander staat verder uitgelegd in het eerste deel van De Grappen van Vroeger. Vaak heeft de strekking te maken met de tweede hoofdzonde: Avaritia (hebzucht). Hij speelt twee rollen: die van eigenrichting, waarbij hij de andere rol. die hij ook speelt, nl. die van rechter, op de korrel neemt. Het gaat dan ook niet alleen om ambiguïteit, maar ook om een vorm van zelfkritiek. Tenminste als je alle mogelijke variaties op een gebeurtenis naast elkaar legt, zoals de toehoorders van deze verhalen verteld op de markt nog konden. Soms werden de variaties door verschillende vertellers naast elkaar verteld, en kon je kiezen met welke strekking je het meest eens was of wie de beste verteller was.

Maar waarom heet dit het verhaal van de Non? De non is een middelaar van Maria, zoals dit in de Middeleeuwen gangbaar was. En zij vertelt dit verhaal in dienst van een priester. Al vlug kom je dan tot de vergelijking van de non met een kip en de priester met een haan. En dan krijgen we iets dat steeds weer in deze verhalen van belang is, de betekenis van de namen. De kip heet Perteloto en de haan heet Canteclaer. Dat je een priester, die zijn verhaal vanaf de kansel verkondigt, kunt vergelijken met een kraaiende haan is wel duidelijk. Maar wat betekent Perteloto. “Perte” staat voor “poort” die zoals we gezien hebben in andere verhalen direct werd geassocieerd met rechtspraak. En “loto” lijkt twee betekenissen te hebben: de eerste is die van “lotus”, of zoals je het zou kunnen uitleggen ”het rad van fortuin”, en daar sluit de tweede betekenis op aan: die van “karma, levenslot, lot”. De non doet haar verhaal dus om te benadrukken dat wij door bemiddeling van Maria ons levenslot een positieve draai kunnen meegeven. Tja, Middeleeuwse literatuur vergt wat uitleg, maar indertijd begreep iedereen het in een oogopslag (naar de hemel). Maar de manier waarop ze bemiddelt, is alles behalve fatsoenlijk zoals verderop te lezen valt (regel 4367–4378): He fethered Pertelote twenty tyme, And trad as ofte, er that it was pryme. De vraag is, werd hier de Maria, de moeder van Jezus, bedoeld of misschien Maria Magdalena als intentie?

(1)De kip heet Perteloto en de haan heet Canteclaer. Dat je een priester, die zijn verhaal vanaf de kansel verkondigt, kunt vergelijken met een kraaiende haan is wel duidelijk. Maar wat betekent Perteloto. “Perte” staat voor “poort” dat zoals we gezien hebben in andere verhalen direct werd geassocieerd met rechtspraak. En “lote” lijkt twee betekenissen te hebben: de eerste is die van “lotus”, of zoals je het zou kunnen uitleggen ”het rad van fortuin”, en daar sluit de tweede betekenis op aan: die van“karma, levenslot, lot”.

Here biginneth the Nonne Preestes Tale of the Cok

and Hen, Chauntocleer and Perteloto.

A POVRE widwe, somdel stope in age,

Was whylom dwelling in a narwe cotage,

Bisyde a grove, stonding in a dale.

This widwe, of which I telle yew my tale,

Sin thilke day that she was last a wyf,

In pacience ladde a ful simple lyf,

For litel was hir catel and hir rente;

By housbondrye, of such as God hir sente,

She fond hir-self, and eek hit doghtren two.

Three large sowes hadde she, and name,

Three kyn, and eek a sheep that highte Malle.

(3) De term die hier in de oorspronkelijke tekst staat, is: “hermes”, wat hieronder in het rood is aangegeven. “Hermes” is voor mij de Griekse God van de handel en humor. Deze Griekse Hermes wordt nogal eens verward met de oosterse Hermes Trismegistos met bijna dezelfde attributen en karaktereigenschappen. Aan wie van beiden Chaucer dacht, is niet uit de tekst op te maken, maar ik denk eerder aan die van de handel dan van de wijsheid. Bij een kip denk je nu eenmaal niet zo vlug aan filosoferen. Het is mij zelfs niet duidelijk, waarom Chaucer deze kippen “hermes” noemt; een Engelse aanduiding voor een kip is het in ieder geval niet.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

A yerd she hadde, enclosed al aboute

A yerd she hadde, enclosed al abouteWith stikkes, and a drye dich with-oute,

In which she hadde a cok, hight Chauntecleer,

In at the land of crowing nas his peer. 4040

His vois was merier than the mery orgon (31)

On messe-dayes that in the chirche gon;

Wel sikerer was his crowing in his logge,

Than is a clokke, or an abbey orlogge.

By nature knew he ech ascencioun 4045

Of equinoxial in thilke toun ;

For whan degrees fiftene were ascended,

Thanne crew he, that it mighte nat ben amended.

His comb was redder than the fyn coral,

And batailed, as it were a eastel-wal. 4050

His bile was blak, and as the Ieet it shoon; (40)

Lyk asur were his legges, and his toon ;

His nayles whytter than the lilie flour,

And lyk the burned gold was his colour.

This gentil cok hadde in his governaunce 4055

Sevene hermes, for to doon al his plesaunce,

Whiche were his sustres and his paramours,

And wonder lyk to him, as of colours.

Of whiche the faireste hewed on hir throte

Was cleped faire damoysele Pertelote. 4060

Curteys she was, discreet, and debonaire, (5I)

And compaignable, and bar hir-self so faire,

Sin thilke day that she was seven night old,

That trewely she hath the herte in hold

Of Chauntecleer loken in every lith ; 4065

He loved hir so, that wel was him therwith.

But such a Ioye was it to here hem singe,

Whan that the brighte sonne gan to springe,

In swete accord, 'my lief is faren in londe.'

For thilke tyme, as I have understonde, 4070

Bestes and briddes coude speke and singe. (60

And so bifel, that in a daweninge,

As Chauntecleer among his wyves alle

Sat on his perche, that was in the halle,

And next him sat this faire Pertelote, 4075

This Chauntecleer gan gronen in his throte,

As man that in his dreem is drecched sore.

And whan that Pertelote thus herde him rore,

She was agast, and seyde, ' 0 herte dere,

What eyleth yow, to grone in this manere? 4080

Ye been a verray sleper, fy for shame !' (7i)

And he answerde and seyde thus, 'madame,

I pray yow, that ye take it nat a-grief:

By god, me metre I was in swich meschief

Right now, that yet myn herte is sore afright. 4085

Now god,' quod he, 'my swevene recche aright,

And keep my body out of foul prisounl

Me mette, how that I romed up and doun

Withinne our yerde, wher-as I saugh a beste,

Was lyk an hound, and wolde ban maad areste 4090

Upon my body, and wolde han had me deed. (8x)

His colour was bitwixe yelwe and reed ;

And tipped was his tail, and bothe his eres,

With blak, unlyk the remenant of his heres;

His snowte smal, with glowinge eyen tweye. 4095

Yet of his look for fete almost I deye ;

This caused me my groning, doutelees.'

'Avoy !' quod she, ' fy on yow, hertelees !

AllasI' quod she, 'for, by that god above,

Now han ye lost myn herte and al my love ; 4100

I can nat love a coward, by my feith. (90

For certes, what so any womman seith,

We alle desyren, if it mighte be,

To han housbondes hardy, wyse, and free,

And secree, and no nigard, ne no fool,4105

Ne him that is agast of every tool,

Ne noon avauntour, by that god above!

How dorste ye seyn for shame unto your love,

That any thing mighte make yow aferd?

Have ye no mannes herte, and han a berd? 4110

Alias! and conne ye been agast of swevenis?

No-thing, god wot, hut vanitee, in sweven is

Swevenes engendren of replecciouns,

And ofte of fume, and of eompleeciouns,

Whan humours been to habundant in a wight. 4II5

Certes this dreem, which ye han met to-night,

Cometh of the grete superfluitee

Of youre rede colera, pardee,

Which causeth folk to dreden in here dremes

Of arwes, and of fyr with rede lemes, 4120

Of grete bestes, that they wol hem byte, (HI)

Of contek, and of whelpes grete and lyre;

Right as the humour of malencolye

Causeth ful many a man, in sleep, to crye,

For fere of blake beres, or boles blake, 4125

Or elles, blake develes wole hem take.

Of othere humours coude I telle also,

That werken many a man in sleep ful wo ;

But I wol passe as lightly as I can.

(5) HUMORALE THEORIE

HUMORALE THEORIE

- Het element “lucht” verwijst naar de Humorale theorie.

- Een vergelijkbare analyse treffen we aan bij Hebreaus (CCCXXVIII):

Iemand kwam bij de dokter en zei hem dat hij last had van een opgeblazen gevoel in zijn buik waardoor hij vaak moest boeren en erg veel scheten liet. Daarop antwoordde de dokter: “Het is zeker een feit dat boeren voortkomen uit een opgeblazen gevoel in je buik, maar wat de scheten betreft, daarvan weet ik tot dit moment niet waar ze vandaan komen!”

- In de Decamerone van Boccaccio (vierde dag, zesde verhaal) staat een andere analyse, gesteund op dezelfde Humorale Theorie (vertaling Frans Denissen, pag 334):

Andreola (had) hem de droom verteld die haar van angstige voorgevoelens had vervuld. Hij lachte haar uit en beweerde dat het onzin was geloof te hechten aan dromen, die immers alleen maar een gevolg zijn van overmatige of onvoldoende voeding en waarvan de ervaring dagelijks uitwijst dat ze bedrog zijn. - Cholerisch is een kenmerk van een Vloeistof uit de Humorale Theorie: gele gal. Zoals hier de werking is beschreven doet het denken aan sodawater, dat door het erin gebrachte koolzuurgas prikkelende bubbels in een vloeistof of sap maakt.

- Melancholie is een temperament, een karakter, in de Humorale Theorie. Het valt het best te vergelijken met wat wij tegenwoordig een depressie noemen.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

As Chauntecleer among his wyves alle

Sat on his perche, that was in the halle,

And next him sat this faire Pertelote, 4075

This Chauntecleer gan gronen in his throte,

As man that in his dreem is drecched sore.

And whan that Pertelote thus herde him rore,

She was agast, and seyde, ' 0 herte dere,

What eyleth yow, to grone in this manere? 4080

Ye been a verray sleper, fy for shame !' (7i)

And he answerde and seyde thus, 'madame,

I pray yow, that ye take it nat a-grief:

By god, me metre I was in swich meschief

Right now, that yet myn herte is sore afright. 4085

Now god,' quod he, 'my swevene recche aright,

And keep my body out of foul prisounl

Me mette, how that I romed up and doun

Withinne our yerde, wher-as I saugh a beste,

Was lyk an hound, and wolde ban maad areste 4090

Upon my body, and wolde han had me deed. (8x)

His colour was bitwixe yelwe and reed ;

And tipped was his tail, and bothe his eres,

With blak, unlyk the remenant of his heres;

His snowte smal, with glowinge eyen tweye. 4095

Yet of his look for fete almost I deye ;

This caused me my groning, doutelees.'

'Avoy !' quod she, ' fy on yow, hertelees !

AllasI' quod she, 'for, by that god above,

Now han ye lost myn herte and al my love ; 4100

I can nat love a coward, by my feith. (90

For certes, what so any womman seith,

We alle desyren, if it mighte be,

To han housbondes hardy, wyse, and free,

And secree, and no nigard, ne no fool, 4105

Ne him that is agast of every tool,

Ne noon avauntour, by that god above!

How dorste ye seyn for shame unto your love,

That any thing mighte make yow aferd?

Have ye no mannes herte, and han a berd? 4100

Alias! and conne ye been agast of swevenis? (,o 0

No-thing, god wot, hut vanitee, in sweven is

Swevenes engendren of replecciouns,

And ofte of fume, and of eompleeciouns,

Whan humours been to habundant in a wight. 4II5

Certes this dreem, which ye han met to-night,

Cometh of the grete superfluitee

Of youre rede colera, pardee,

Which causeth folk to dreden in here dremes

Of arwes, and of fyr with rede lemes, 4120

Of grete bestes, that they wol hem byte, (HI)

Of contek, and of whelpes grete and lyre;

Right as the humour of malencolye

Causeth ful many a man, in sleep, to crye,

For fere of blake beres, or boles blake, 4125

Or elles, blake develes wole hem take.

Of othere humours coude I telle also,

That werken many a man in sleep ful wo ;

But I wol passe as lightly as I can.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

But nathelees, as touching daun Catoun, 050

That hath of wisdom such a greet renoun.

Though that he bad no dremes for to drede,

By god, men may in olde bokes rede

Of many a man, more of auctoritee 4165

Than ever Catoun was, so mote I thee,

Than al the revers seyn of his sentence.

(8) Van “Mulier est hominus confusio” zijn verschillende vertalingen mogelijk, maar geen komt maar enigszins in de buurt van wat Chaucer er ironisch genoeg van heeft gemaakt. De eerste vertaling zou kunnen zijn: de vrouw is de man tot schande. Of misschien: de vrouw is een mix van mannelijke en vrouwelijke eigenschappen, kortom: zonder de man zou ze er niet zijn. Of, ten slotte: de vrouw brengt mannen in verwarring. Een erg positief vrouwbeeld houdt de haan er blijkbaar niet op na.

(9) Zie noot een: uitleg bij de naam Perteloto.

(10) “Chuck” met zijn associatie in het Engels met Chick (meisje) en Chicken (kip) is in het Nederlands onvertaalbaar. Het is des te meer onvertaalbaar, omdat het een onomatopee is: kippen in verlegenheid gebracht brengen inderdaad een vergelijkbaar geluid uit.

(11) Dit is een uitleg bij pryme (zie hieronder), de gebedstijden van een klooster.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

Madame Pertelote, so have I blis,

Of o thing god hath sent me large grace;

For whan I see the beautee of your face, 4350

Ye ben so scarlet-reed about your yën, (340

It maketh al my drede for to dyen;

For, also siker as In principio,

Muller est hominis confusio ;

Madame, the sentence of this Latin is-- 4355

Womman is mannes Ioye and al his blis.

For whan I fele a-night your softe syde,

Al-be-it that I may nat on you ryde,

For that our perche is maad so narwe, alas!

I am so ful of Ioye and of solas 4360

That I defye bothe sweven and dreem.'

And with that word he fley doun fro the beem,

For it was day, and eek his henries alle ;

And with a chuk he gan hem for to calle,

For he had founde a corn, lay in the yerd. 4365

Royal he was, he was namore aferd ;

He fethered Pertelote twenty tyme,

And trad as ofte, er that it was pryme.

He loketh as it were a grim leoun;

And on his toos he rometh up and doun, 4370

Him deyned not to sette his foot to grounde. (36_)

He chukketh, whan he hath a corn y-founde,

And to him rennen thanne his wyves alle.

Thus royal, as a prince is in his halle,

Leve I this Chauntecleer in his pasture ; 4375

And after wol I telle his aventure.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

That in the grove hadde woned yeres three,

By heigh imaginacioun fom-cast,

The same night thurgh-out the hegges brast

Into the yerd, ther Chauntecleer the faire

Was wont, and eek his wyves, to repaire ; 4410

And in a bed of wortes stifle he lay, (4ol)

Til it was passed undern of the day,

Wayting his tyme on Chauntecleer to falle,

As gladly doon thise homicydes alle,

That in awayt liggen to mordre men. 4415

O false mordrer, lurking in thy den!

(14) Ik kon niet nalaten hier een anachronisme in de vertaling toe te voegen.

(15) Ecclesiasticus valt op twee manieren uit te leggen. Voor elke uitleg heb ik hier een link opgenomen. De eerste uitleg gaat terug op een tijd voor de geboorte van Jezus, ongeveer 180 jaar voor de geboorte van Jezus, of misschien heeft het te maken met een deel Prediker uit de joodse Bijbel.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

Lyth Pertelote, and alle hir sustres by,

Agayn the sonne; and Chauntecleer so free

Song merier than the mermayde in the see ; 4460

For Phisiologus seith sikerly, (45I)

How that they singen wel and merily.

And so bifel that, as he caste his yë,

Among the wortes, on a boterflye,

He was war of this fox that lay ful lowe. 4465

No-thing ne liste him thanne for to erowe,

But cryde anon, 'cok, cok,' and up he sterte,

As man that was affrayed in his herte.

For naturelly a beest desyreth flee

Fro his contrarie, if he may it see, 4470

Though he never erst had seyn it with his yë (460

This Chauntecleer, whan he gan him espye,

He wolde han fled, but that the fox anon

Seyde, 'Gentil sire, alias! wher wol ye gon?

Be ye affrayed of me that am your freend? 4475

Now certes, I were worse than a feend,

If I to yow wolde harm or vileinye.

I am nat come your counseil for tespye;

But trewely, the cause of my cominge

Was only for to herkne how that ye singe. 4480

For trewely ye have as mery a stevene (47x)

As eny aungel hath, that is in hevene ;

Therwlth ye han in musik more felinge

Than hadde Boece, or any that can singe.

My lord your fader (god his soule blesse !) 4485

And eek your moder, of hir gentilesse,

Han in myn hous y-been, to my gret ese;

And certes, sire, ful fayn wolde I yow plese.

But for men speke of singing, I wol saye,

So mote I brouke wel myn eyen tweye, 4490

Save yow, I herde never man so singe, (48x)

As dide your fader in the morweninge ;

Certes, it was of herte, al that he song.

And for to make his voys the more strong,

He wolde so peyne him, that with bothe his yen 4495

He moste winke, so loude he wolde cryen,

And stonden on his tiptoon ther-with-al,

And strecche forth his nekke long and smal.

And eek he was of swich discrecioun,

That ther has no man in no regioun 4500

That him in song or wisdom mighte passe. (49 I)

I have wel rad in daun Burnel the Asse,

Among his vers, how that ther was a eok,

For that a preestes sone yaf him a knok

Upon his leg, whyl he was yong and nyce, 4505

He made him for to lese his benefyee.

But certeyn, ther nis no comparlsoun

Bitwix the wisdom and discrecioun

Of youre fader, and of his subtiltee.

Now singeth, sire, for seinte charitee, 4510

Let see, conne ye your fader eountrefete?' (5o_)

This Chauntecleer his winges gan to bete,

As man that coude his tresoun nat espye,

So was he ravisshed with his flaterye.

Alias! ye lordes, many a fals flatour 4515

Is in your courtes, and many a losengeour,

That plesen yow wel more, by my feith,

Than he that soothfastnesse unto yow seith.

Redeth Ecclesiaste of flaterye ;

Beth war, ye lordes, of hir trecherye. 4520

Thin Chauntecleer stood hye up-on his toos, (511)

Strecching his nekke, and heeld his eyen cloos,

And gan to crowe loude for the nones;

And daun Russel the fox sterte up at ones,

And by the gargat hente Chauntecleer, 4525

And on his bak toward the wode him beer,

For yet ne was ther no man that him sewed.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

Was never of ladies maad, whan Ilioun

Was wonne, and Pirrus with his streite swerd,

Whan he hadde hent king Priam by the berd,

And slayn him (as saith us £neydos),

As maden alle the hennes in the clos, 4550

Whan they had seyn of Chauntecleer the sighte. (540

But sovereynly dame Pertelote shnghte,

Ful louder than dide Hasdrubales wyf,

Whan that hir housbond hadde lost his lyf,

And that the Romayns hadde brend Cartage.

(18)(Overgenomen uit bewerking in modern Engels) “Jack Straw was one of the leaders of the riots in London during the Peasants′ Revolt of 1381, according to Walsingham′s Chronicle. He and his gang massacred a number of Flemings in the Vintry, and he was leter captred en decaptated.” Dit is in dezelfde tijd als waarin Robin Hood ten tonele verschijnt. In hoeverre Jack Straw iets met Robin Hood te maken heeft, heb ik nergens kunnen terugvinden, hoewel het nogal voor de hand ligt.

Oorspronkelijke tekst

This sely widwe, and eek hir doghtres two, 4565

Herden thise hennes crye and maken wo,

And out at dores sterten they anoon,

And syen the fox toward the grove goon,

And bar upon his bak the cok away;

And cryden, ' Out ! harrow ! and weylaway ! 4570

Ha, ha, the fox!' and after him they ran, (560

And eek with staves many another man ;

Ran Colle our dogge, and Talbot, and Gerland,

And Malkin, with a distal in hir hand ;

Ran cow and calf, and eek the verray hogges 4575

So were they fered for berking of the dogges

And shouting of the men and wimmen eke,

They ronne so, hem thoughte hir herte breke.

They yelleden as feendes doon in here ;

The dokes cryden as men wolde hem quelle; 4580

The gees for fere flowen over the trees; (570

Out of the hyve cam the swarm of bees ;

So hidous was the noyse, a! benedicite

Certes, he Iakke Straw, and his meynee,

Ne made never shoutes half so shrille, 4585

Whan that they wolden any Fleming kille,

As thilke day was maad upon the fox.

Of bras thay broghten bemes, and of box,

Of horn, of boon, in whiche they blewe and pouped,

And therwithal thay shryked and they houped; 4590

It semed as that heven sholde falle. (580

Now, gode men, I pray yow herkneth alle!

Lo, how fortune turneth sodeinly

The hope and pryde eek of hir enemy!

This cok, that lay upon the foxes bak, 4595

In al his drede, un-to the fox he spak,

And seyde, 'sire, if that I were as ye,

Yet sholde I seyn (as wis god helpe me),

Turneth agayn, ye proude cherles alle!

A verray pestilence up-on yow falle! 4600

Now am I come un-to this wodes syde, (590

Maugree your heed, the cok shal heer abyde ;

I wol him ere in feith, and that anon.'–

The fox answerde, 'in feith, it shal be don,'–

And as he spak that word, al sodeinly 4605

This cok brak from his mouth deliverly,

And heighe up-on a tree he fleigh anon.

And whan the fox saugh that he was y-gon,

' Alias !' quod he, ' O Chauntecleer, alias

I have to yow,' quod he, 'y-doon trespas, 4610

In-as-muche as I maked yow aferd, (600

Whan I yow hente, and broghte out of the yerd ;

But, sire, I dide it in no wikke entente ;

Corn doun, and I shal telle yow what I mente.

I shal seye sooth to yow, god help me so.'

'Nay than,' quod he, 'I shrewe us bothe two,

And first I shrewe my-self, bothe blood and bones,

If thou bigyle me ofter than ones.

Thou shalt na-more, thurgh thy flaterye,

Do me to singe and winke with myn y& 4620

For he that winketh, whan he sholde see, (6H)

A1 wilfully, god lat him never thee!'

'Nay,' quod the fox, ' but god yeve him meschaunee,

That is so undiscreet of govemaunce,

That Iangleth whan he sholde holde his pees.'